Reviving a digital piano with new brains

2024-05-17

One day, I was playing my Roland HP-1500 digital piano, which is an incredibly old model. It suddenly started making weird electrical noises, and then it died. I opened the piano up, and looked at the circuit board, but my efforts to figure out what went wrong were ultimately futile.

At this point, I had a thought: maybe I could build a brand new circuit for the piano, replacing the broken original board. After all, how hard could it be? I had just learned the basics of electronics, and this definitely seemed like a good learning experience.

That was a few months ago. Recently, I finished implementing this project, which I named geode-piano. Here is a quick demo of it (excuse the poor microphone quality):

This project is powered by a single Raspberry Pi Pico, which runs firmware written in Rust. Source code and build instructions are available on the project repository.

It took quite a while to get to this point, and so this blog post will document the process of designing and implementing geode-piano.

How a digital piano works

First, before even designing anything, I did a bit of research on what was going on inside a digital piano. This helps understand how feasible the project is and how complicated it will be.

As it turns out, digital pianos are, electrically, pretty simple. The switches that detect key-presses aren’t that different from a regular push-button: when pressed, they let power through, which we can detect.

However, there’s 88 keys on a typical piano, and that’s a lot of switches to deal with. The microcontroller (processor chip) inside the piano usually can’t handle that many inputs.

This can be solved with a key matrix, a specific wiring design. Essentially, a key matrix helps cram all those key switches onto a microcontroller with way less input pins. For example, look at this key matrix:

column

1 2 3 4

row

│ │ │ │

1 ─┼─┼─┼─┼

2 ─┼─┼─┼─┼

3 ─┼─┼─┼─┼

Columns are a power source, and rows are inputs. We hook up all of these wires to the microcontroller.

Each intersection in this grid has a switch. When a switch is on, power can flow (in only one way) from the column into the row.

The key matrix works by scanning each column sequentially. By detecting which rows are powered, we can deduce which switches were pressed.

column column

1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4

row ↓ row ↓

┃ │ │ │ │ ┃ │ │

1 ━╋━┿━┿━┿ 1 ─┼─╂─┼─┼

2 ─╂─┼─┼─┼ 2 ━┿━╋━┿━┿ and so on...

3 ━╋━┿━┿━┿ 3 ─┼─╂─┼─┼

switches pressed: switches pressed:

- C1R1 - C2R2

- C1R3

This scan is quite fast, usually taking less than a few milliseconds. Using this matrix, we need 8 pins, while an equivalent non-matrix circuit would need 12 pins. However, we sacrifice a bit of speed because we scan column by column rather than all switches at once.

In the digital piano, these switches are hooked up to the piano keys, allowing key-presses to be detected. On my piano, we have 176 key-switches (for reasons which I will explain later), which can be scanned using only 40 pins thanks to the matrix.

Note: this diagram and explanation are both simplified, so click here for a more detailled explanation. In practice, diodes are used to ensure power doesn’t flow the wrong way.

So that’s how a digital piano works, theoretically. What does that look like, under the hood? As it turns out, the matrix is accessible through ribbon cables (or flat flexible cable, or FFC).

The metallic contacts on these cables correspond to the columns and rows of the key matrix. Usually, you’ll find one or multiple ribbon cables with one end plugged into the main board of the digital piano, and the other ends leading inside the piano key mechanism.

Project architecture

geode-piano works by disconnecting the ribbon cables from the original circuit board, then reconnecting them into my own circuit. Effectively, I’m taking over the piano key circuitry.

Designing this, I tried to make things as easy as possible for me. Therefore, this project only exposes the piano as a MIDI controller. This means that we will only be transmitting data about what note was pressed when. Meanwhile, on a computer, we can make use of existing software to synthesize the actual piano sound from this data.

╭─────────────╮ ribbon cables ╭──────────────────╮

│ geode-piano ├─────────────────┤ piano key matrix │

╰──────┬──────╯ ╰──────────────────╯

│

│

│ midi over usb

│

│

╭───────┴──────────╮

│ software sampler │

│ (in a laptop) │

╰───────┬──────────╯

│

│ 3.3mm or usb or whatever

│

╭───────┴───────────╮

│ speaker/headphone │

╰───────────────────╯

This is in contrast to actually generating the sound in my circuit and also playing it through a speaker, like the original board did.

I personally think that this architecture is the fastest way to get to a working product. After all, convincingly synthesizing a piano sound is difficult, so reinventing this wheel would be unwise.

Hardware

Now, physically, what does that [geode-piano] box in the architecture diagram above look like?

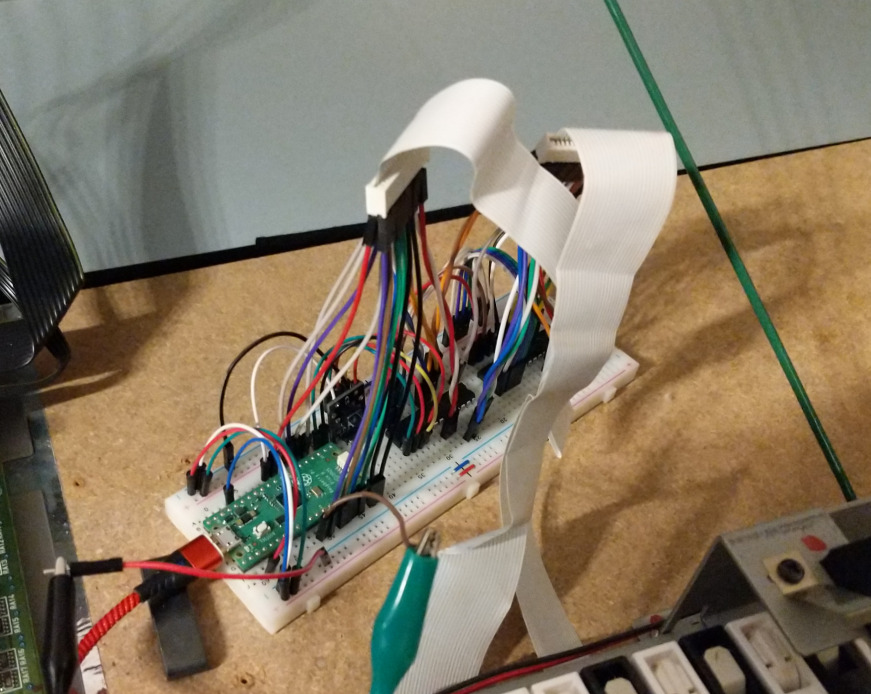

The answer is that it looks like a mess.

Microcontroller

First of all, the heart of geode-piano is the Raspberry Pi Pico microcontroller, which is the green chip in the image above. I had a few laying around, so it was the obvious choice for me to use. This part actually runs the firmware, does all the processing, and also connects back to a computer via a micro-USB port.

Sockets

Then, there are the sockets above. Those are actually FFC sockets, which the ribbon cables can be plugged into. This is definitely one of the cursed parts of this project, because these sockets are designed to be soldered, and not to be used with jumper cables. In fact, I had to slice off the tips of a bunch of female-to-male jumper cables to get them to connect to the pins. I am still quite surprised that the pins snap perfectly in the female ends.

This arrangement of many jumper cables in parallel going up to the sockets was also a bad idea, as it caused crosstalk. In tests, it showed up as ghost signals being detected with no visible source. Twisting some wires together and attempting to space them out fixed this issue.

As an aside, I originally bought the wrong size of socket due to carelessness. I put up a ruler to the contacts and eyeballed the pin pitch (distance between each contacts’ centers), and decided it was 1.0mm. This was a big mistake on my part, as I found out later that it was 1.25mm.

After this, I discovered that the socket specsheets had measurements of the distance between the first and last contacts, which is easier and less error-prone to measure with a typical ruler. Actually reading these documents should help me avoid these kinds of mistakes.

Pin extenders

The astute among you might have noticed that a Pico microcontroller does not have enough input pins for this project. To remedy this issue, I used two MCP23017 chips, which are pin extenders. Each has 16 GPIO pins, and they communicate over I²C to the Pico, which requires only 2 pins on that end. For these 14 extra pins we get, we sacrifice a bit of convenience and efficiency.

One of the features of these chips is their capacity for both input and output. This is important because I don’t actually know which contact on the ribbon cable corresponds to which row and column. Instead of reverse-engineering the circuitry with a multimeter, I made a scanner that will try every row/column combination possible for each key until it finds a valid one. With this information, we can reconstruct the key matrix pinout.

A few important tips I would tell past me about this chip:

- You need pull-up resistors for I²C. I won’t go into detail about it because the linked blog post sums up my experience with this.

- Multiple I²C peripherals can live on the same bus.

- Plug the

RESETpin into the positive power rail. I was stuck for an entire afternoon because no documentation said this clearly. In the datasheet, “must be externally biased” means “do not leave this pin floating under any circumstances”. Also, the overbar on the pin name in the datasheet means that pulling the pin low will cause a reset.- MCP23017 chips are known to have weird behaviour on pins GPA7 and GPB7. (Look at the most recent datasheet, not the old one!)

Firmware

If you’ve used microcontrollers before, you probably know that they’re programmed using C++, C, or MicroPython, or some similar language. The Raspberry Pi Pico is no different, as the most common ways to write firmware for it are the Pico C SDK, and MicroPython.

I had tried C before, but the tooling was painful to deal with. My language server clangd would display unfixable errors about missing imports and unknown functions. This was fine, but it was really annoying. MicroPython does seem quite user-friendly, but for scanning the key matrix, it could be problematic due to performance concerns.

In the end, I settled on using Rust. This option seems relatively obscure and less well documented, however it ended up working well for me.

The main advantage of Rust for me is that it is a modern, yet quite performant language.

Even in a no_std embedded environment, you have a full package manager to easily install libraries.

The MCP23017 library, for example,

let me develop that part of the code faster.

Also, rust-analyzer works perfectly well, and

gives the most detailled and helpful messages out of all language servers I’ve used before.

Specifically for this project, I used the embassy-rs framework. This library makes embedded development in Rust really easy. It offers drivers for a bunch of useful features, like USB MIDI, USB logger output, I²C and many others. Embassy also works using async/await, which makes multitasking simple and elegant. I’m not a Rust expert, though, so consult their website for more information about this.

Even though Rust is great, it does have an infamously steep learning curve. As you might know, Rust is memory-safe by using a strict borrow checker. If you follow its rules, you can eliminate many types of memory bugs. In this project, though, I spent many hours fighting Rust’s borrow checker. What I learned from this experience is that, when possible, you should follow Rust’s idiomatic ways of solving problems. This means that you should avoid long-lived references, and keep lifetimes short. Essentially, don’t overcomplicate the program logic.

Anyways, the source code for geode-piano’s firmware is available on the project repository.

Other features

That was the general overview of the project. These are a few miscellaneous details that I could not fit well elsewhere.

Velocity detection

A digital piano is, electronically, just a bunch of buttons that trigger sound when pressed. There is, however, a slight nuance to this. A button switch has only two states, on and off. On a piano, hitting a key really hard makes a loud note, and softly pressing it makes a soft note. From the perspective of our hardware, a button press is just a button press; there is no information about intensity.

To measure the intensity of key-presses, some engineer decided that instead of every key having one switch, they should have two switches. These switches are placed so that they trip one after the other during a keypress. By measuring the time between the switches’ activations, the digital piano can estimate the intensity of a press. A fast press is a hard press, and a slow press is a soft press. This system works well, and is present in most digital pianos.

geode-piano does have velocity detection too, but it is not very precise. I think this is because it takes too long for the key matrix scan (around 7ms), which is not fine-grained enough to accurately detect velocity. Possibly, it is because of the MCP23017 being too slow, but it could also be my code. At this point though, the piano works well enough that I do not feel it is worth it to optimise this.

Sustain pedal

Pianos have pedals that control the sound. The code for handling this is not quite different from handling regular keys. However, connecting the pedal to the microcontroller is more difficult. Typically, the pedals are connected to the piano via a TRS jack (not dissimilar to a headphone jack). However, I had no socket component for this type of plug. Therefore, I made the most cursed part of the circuit:

The brown wire is stripped on the part where it wraps around the plug, and the yellow and pink parts are stripped paperclips. This may seem like a fire hazard, but the wire connected to an input pin, so unless the microcontroller uses the wrong pins (in which case we have bigger problems) there should be no short-circuit risk.

In my experience so far, this connection actually works remarkably well. Another win for terrible wiring.

Conclusion

This project was pretty fun to do. Before starting it, I thought that it was pretty ambitious for my skill level; at the time, I’d only played with wiring LEDs and buttons up to my microcontroller. Who knew that I could implement the circuitry for an entire digital piano?

I did learn a lot about electronics through this project, as well as a bit of Rust. I don’t remember where I heard it anymore, but I agree with the notion that you should try projects like this that are just barely within your capacities to accomplish. This kind of hands-on learning is one of the better ways to develop problem-solving skills.

Anyways, I now have a working piano again!

dogeystamp

dogeystamp